By Kathleen Campbell Walker (1)

Keeping it simple is often a key goal in any compliance policy for a company, but sometimes it may not be a best practice and indeed could cause a company to incur liability. Employers should consider onboarding personnel products carefully and it is important not to overlook if such products attempt to address the conundrum of Form I-9 completion.

Background

As an introduction, the Form I-9 has been around as a requirement for employers in the hiring process since 1986. Employers must determine the identity and work authorization of all new hires as of November 7, 1986. Section 1 of the Form I-9 is completed by the employee, but the employer is responsible for making sure the employee has completed Section 1 properly. For example, employers not enrolled in E-Verify may NOT mandate that the employee provide their social security number in the blank provided in Section 1. If the employee does not have a social security number (SSN) or does not wish to provide it on the Form I-9, he or she can choose not to provide the number in Section 1 and provide a List A or List C document that establishes work authorization for Section 2. So, how to deal with tax withholding, well - that is a separate tax issue addressed with the completion of a Form W-4

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) notes that employers are required to obtain the employee’s name and SSN to complete the Form W-2 and the W-4 when the new employee starts work. Employers should ask an employee to present his or her social security card when the W-4 is completed, but the employee is not required to show the card. An employee without a social security card should apply for a social security card using Form SS-5. The IRS admonishes employers not to accept an ITIN (Taxpayer Identification Number) in place of an SSN. An ITIN is a 9-digit number beginning with the number “9” and has a format like an SSN (NNN-NN-NNNN). When the employee does not have a SSN, the IRS advises employers to enter all zeroes in the SSN block, if filing a W-2 electronically or on magnetic data or to enter the phrase, “applied for,” if applicable, in the box (a) on paper W-2 forms. Later, when an employee provides a SSN, a Form W-2c is filed by the employer with the Social Security Administration (SSA) as to the new SSN assigned.

A job applicant can be work authorized without a SSN.

What the execution of Section 1 means for an Employee

Individuals can be subject to prosecution for knowingly and willfully entering false information on Form I-9. For example, when employees sign Section 1 of Form I-9, they are attesting under penalty of perjury that the information provided by them in Section 1, including their citizenship or immigration status selected, is complete, true, and correct. In addition, the employee’s signature on the Form I-9 is also an acknowledgment that he or she is aware of the severe penalties provided by law, including possible criminal prosecution for knowingly and willfully making false statements or using false documentation when completing a Form I-9. In addition, the employee is acknowledging in signing Section 1 of Form I-9 that falsely attesting to U.S. citizenship may subject him or her to penalties, removal proceedings, as well as adversely affecting his or he ability to seek future immigration benefits.

It is also important to note that employers must ensure that all pages of the current Form I-9, its instructions, and the List of Acceptable Documents are available, in print or electronically, to all employees completing Form I-9. As a further cautionary note, Section 1 must never be completed before a job applicant has accepted a job offer from the employer.

So what if an onboarding software uses the information provided by an employee to auto (pre) - populate portions of the Form I-9?

The challenge is that the employee must be provided the instructions to Form I-9 when completing Section 1 and attest under penalty of perjury as to the potential consequences mentioned above for the knowing and willful failure to accurate and truthful information or documentation in the completion of the Form I-9. Would it be acceptable to provide even a name on the Form I-9 from the onboarding software without the employee being made aware of the consequences when the information appears on the Form I-9? As long as the Form I-9 instructions and the Form I-9 itself is available for review and completion in the onboarding process, is that sufficient?

It is important to remember the tale of the retailer, Abercrombie & Fitch, when considering Form I-9 automation. In September of 2010, Abercrombie & Fitch paid a settlement fine of $1,047,110.00 for Form I-9 violations due to numerous technology-related errors in their electronic Form I-9 verification system, which resulted in the Forms I-9 not being considered as properly completed. Apparently, one of the errors included the inability of government auditors from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to readily access and print out readable Forms I-9 in compliance with the regulations.

What has the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) said on this auto (pre) - population issue?

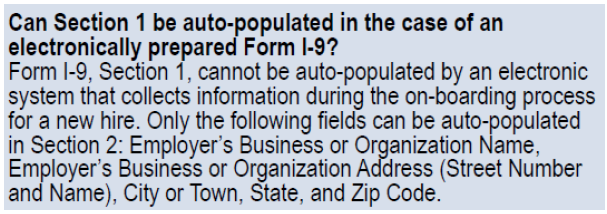

First of all, unlike the IRS (e.g. e-file provider), there is no vendor approval process for a Form I- 9 software vendor. In Issue 33 of the E-Verify Connection publication (October 31, 2016), it provided the following statement:

That response seems like a clear, “NO,” on Section 1 pre-population.

In 2011, ICE indicated that Section 1 pre-population was appropriate if the employer also completed the Preparer/Translator portion of Section 1. In April of 2013, however, ICE indicated in liaison meetings with the American Immigration Lawyers Association that it is never permissible to pre-populate Section 1, even if the employee inputted the data causing the pre-population of the Form I-9. Later in the fall of 2013, ICE modified its prior comment by indicating that it …, “had no official position on pre-population.” ICE confirmed in a recent liaison meeting with AILA in November of 2018 that, “… the appropriate agency for guidance on completing the I-9 is DHS/USCIS.”

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS), which hosts the I-9 Central website, indicated in 2012 that if Section 1 of the Form I-9 is pre-populated, then the employer must make sure that the Preparer/Translator portion of Section 1 is completed. Later in 2013, USCIS representatives in a stakeholder teleconference noted that an employer SHOULD NOT electronically pre-populate Section 1 of the Form I-9, even if the employee reviewed the pre-populated information before signing Section 1. USCIS then published the E-Verify newsletter in 2016 mentioned above, which allowed some fields to be pre-populated for Section 2 – not 1. Of course, ICE, the usual auditor and enforcer of Form I-9 compliance has not indicated any adoption of this interpretation by USCIS other than its statement of deference to USCIS policy.

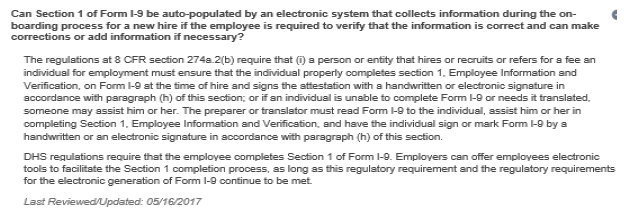

I-9 Central provides the following guidance in its Questions and Answers section, which was updated on May 16, 2017:

This guidance is muddy at best, but seems to support the use of the Preparer/Translator part of Section 1, if pre-population occurs.

The Office of Special Counsel of the DOJ (now known and the Immigrant and Employee Rights Section), which enforces the anti-discrimination rules concerning Form I-9 completion, indicated in one of its Technical Assistance Letters (TALs) dated August 20, 2013, that pre-population is not recommended due to the increased possibility of inaccurate or outdated information being placed in Section 1. In addition, OSC warned that pre-populating Section 1 potentially increased the possibility that a new hire not proficient in English would not understand, which would require the use of the Preparer/Translator part of Section 1. In November of 2018, the Immigrant and Employee Rights (IER) section outlined the following software issues that pose anti-discrimination risks:

IER sees a wide variety of software issues. Examples include: drop down menus that may restrict choice of documents that employees can present; software that limits workers’ abilities to edit information; pop-up windows that advise employers to verify information associated with citizenship status; and messages that imply that employers should be requesting additional documents that are not required or may alert or flag people for reverification when people should not be reverified. IER noted that manuals or training regarding software may also give incorrect guidance or incorrectly state the law. IER cited examples of settlements related to electronic I-9 software including a Macy’s settlement in 2013 and a Panda Express settlement in 2017. The Macy’s Florida Store settlement agreement terms required Macy’s to pay a civil penalty of $175,000.00 and one of the included settlement requirements was to modify its electronic Form I-9 system to permit employees to complete Section 1 of the Form I-9. The Panda Restaurant Group’s settlement for $400,000.00 required the company to modify is electronic Form I-9 system to allow those employees selecting the, “Alien Authorized to Work,” citizenship attestation in Section 1 of the Form I-9 to write, “N/A,” in the Section 1 expiration date field.

As to pre-population, IER noted that it would defer to DHS regarding whether a software allowing employees to edit fields once completed would be acceptable, but that it continues to see problems relating to pre-population that may or may not relate to discrimination.

What is the risk of getting this pre-population issue wrong?

As noted above, a company can be exposed to significant civil penalties as to completion of the Form I-9 as well as potential discrimination related penalties in its hiring practices. So what should employers do about onboarding programs, which take any portion of an employment application and use that data to populate portions of Section 1 of the Form I-9?

1. The most conservative approach is to separate the Form I-9 from the rest of the onboarding process. The employee must be provided the complete current instructions for the Form I-9 and the Form itself for review. Note that USCIS has a Spanish version of the Form I-9 and its instructions for reference as well. Of course, only employers in Puerto Rico may actually use the Spanish Form I-9 for completion.

2. The next option might be to rely on the USCIS response from its Questions and Answers section on I-9 Central combined with the 2016 E-Verify Connection publication mentioned above to approach the Section 1 challenge as follows:

• Include a notice and warning in the onboarding software to allow the employee to

agree in writing that specific information such as his or her name, date of birth, and address provided during onboarding can be used to pre-populate his or her Form I-9.

• Also, provide a link to the Form I-9 and its instructions, which must be available at the time the employee elects to allow the data specified to pre-populate the Form I-9.

• Require the employer to complete the Preparer/Translator part of Section 1 of the Form I-9, since the onboarding system “helped” the employee complete the Form.

• Make sure the employee can edit and accept Section 1 responses in the Form I-9 itself and submit those changes with his or her electronic signature.

This option 2 outline makes the more conservative option appear more attractive. Of course, ICE and USCIS refuse to vet any program as acceptable so the option is merely theoretical.

The bottom line for employers is that legal counsel is consulted as to any Form I-9 pre-population function of an onboarding program, which must be closely scrutinized for potential exposure to liability due to its use. In addition, Section 1 requirements for E-Verify employers must be understood.

ELPASO 99998-3204 17261v1

(1) Kathleen Campbell Walker is a member of Dickinson Wright PLLC and serves as a co-chair of the Immigration Practice Group. http://www.dickinson-wright.com/ She is a former national president and general counsel of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) and is Board Certified in Immigration and Nationality Law by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization. She serves on the AILA Board of Governors. In 2014, she received the AILA Founder’s Award, which is awarded from time to time to the person or entity, who has had the most substantial impact on the field of immigration law or policy in the preceding period (established 1950). She has testified several times before Congress on matters of immigration policy and border security.